NB02a Mass Spectrometry Based Proteomics

- Mass spectrometry (MS)-based proteomic

- References

Mass spectrometry (MS)-based proteomic

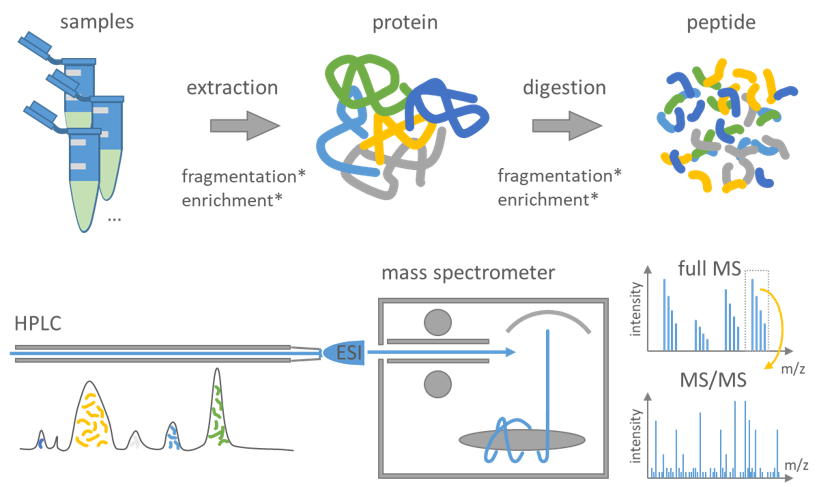

Figure 3: Summary of a typical proteomics workflow following the bottom-up principle.

During sample preparation proteins are extracted from the samples and digested into peptides using proteases typically trypsin. An optional fractionation or enrichment may be applied at either the protein or peptide level to enhance the scope of identification. Peptides are separated by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and afterward transferred into the vacuum of the mass spectrometer mostly using electrospray ionization (ESI). Cycles of full MS including all peptide at a time followed by MS/MS of selected peptides are measured. The consecutive measured MS and MS/MS spectra are then used to computationally identify and quantify the peptide sequence and infer the protein.

The proteome is understood as an entire complement of proteins in one cell, tissue or a whole organism. Proteomics as a scientific field deals with the qualitative and quantitative analysis of protein expression patterns. Thus, proteomics relies primarily on the ability to unambiguously identify proteins, followed by accurate quantification. Mass spectrometry-based proteomics refers to the large-scale analysis of proteins using mass spectrometry, an analytical method to determine the mass of molecules. In the case of proteomics, the target molecules are whole proteins or peptides.

The typical proteomics workflow is as follows (Figure 3): First, proteins are isolated from cells or tissues by lysis followed by biochemical fractionation or affinity selection. MS on whole proteins (top-down proteomics) is less sensitive and more difficult to handle when compared to MS on peptides (bottom-up proteomics), as the mass of the intact protein by itself is insufficient for protein identification (Breuker et al. 2008, Reid and McLuckey 2002). Therefore, the bottom-up approach is standardly used, which comprises the enzymatic degradation of proteins to peptides using an endopeptidase (trypsin in most cases) (Olsen et al. 2004). Trypsin is advantageous as it generates peptides with C-terminally protonated amino acids to foster the detectability of a full ion ladder (series) in a subsequent, optional fragmentation step for sequencing. The peptides are separated by one or more steps of liquid chromatography (LC) and afterwards transferred into the vacuum of the mass spectrometer, where a mass spectrum of the peptides eluting at this time from the LC is taken (MSU+00B9 spectrum or ‘normal mass spectrum’). A prioritized list of these peptides for fragmentation is either automatically generated or provided by the operator. These peptide ions are then fragmented by energetic collision with an inert gas and recorded as tandem MS spectra (MS/MS or MSU+00B2 spectra). The consecutive MS and MS/MS spectra are then used to computationally identify the peptide’s sequence and quantify its abundance (Walther and Mann 2010, Aebersold and Mann 2003).

References

- Breuker, K., Jin, M., Han, X., Jiang, H. & McLafferty, F. W. Top-down identification and characterization of biomolecules by mass spectrometry. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry 19, 1045–1053; 10.1016/j.jasms.2008.05.013 (2008).

- Reid, G. E. & McLuckey, S. A. 'Top down' protein characterization via tandem mass spectrometry. Journal of mass spectrometry : JMS 37, 663–675; 10.1002/jms.346 (2002).

- Olsen, J. V., Ong, S.-E. & Mann, M. Trypsin cleaves exclusively C-terminal to arginine and lysine residues. Molecular & cellular proteomics : MCP 3, 608–614; 10.1074/mcp.T400003-MCP200 (2004).

- Walther, T. C. & Mann, M. Mass spectrometry-based proteomics in cell biology. J. Cell Biol. 190, 491–500; 10.1083/jcb.201004052 (2010).

- Aebersold, R. & Mann, M. Mass spectrometry-based proteomics. Nature 422, 198–207; 10.1038/Nature01511 (2003).