NB04b Peptide Identification

- Understanding peptide identification from MS2 spectra

-

Matching and scoring of Tandem MS peptide identification

- Step 1: Data acquisition and preprocessing

- Step 2: Preselecting the peptides of interest

- Step 3+4: Matching and Scoring

Understanding peptide identification from MS2 spectra

Under low-energy fragmentation conditions, peptide fragment patterns are reproducible and, in general, predictable, which allows for an amino acid sequence identification according to a fragmentation expectation. Algorithms for peptide identification perform in principle three basic tasks:

(i) a raw data preprocessing step is applied to the MS/MS spectra to obtain clean peak information. The same signal filtering and background subtraction methods are used as discussed in the section of low-level processing. Peak detection, however, may be performed differently. Preprocessing of MS/MS spectra focuses on the extraction of the precise m/z of the peak rather than the accurate peak areas. The conversion of a peak profile into the corresponding m/z and intensity values reduces the complexity, its representation is termed centroiding. To extract the masses for identification in a simple and fast way, peak fitting approaches are used. These approaches take either the most intense point of the peak profile, fit a Lorentzian distribution to the profile, or use a quadratic fit.

(ii) Spectrum information and possible amino acid sequences assignments are evaluated.

(iii) The quality of the match between spectrum and possible sequences is scored.

Even though the three steps roughly describe the basic principle of algorithms used for peptide sequence identification, most implementations show differences in individual steps which can lead to major changes in the outcome. Therefore, it has been proven useful to utilize more than one algorithm for a robust and thorough identification. Due to their major difference in identification strategies and prerequisites, identification algorithms are normally classified into three categories: (i) de novo peptide sequencing, (ii) peptide sequence-tag (PST) searching, and (iii) uninterpreted sequence searching. However, in this notebook we focus on the explanation of (iii) uninterpreted sequence searching, the most frequently used methods.

Matching and scoring of Tandem MS peptide identification

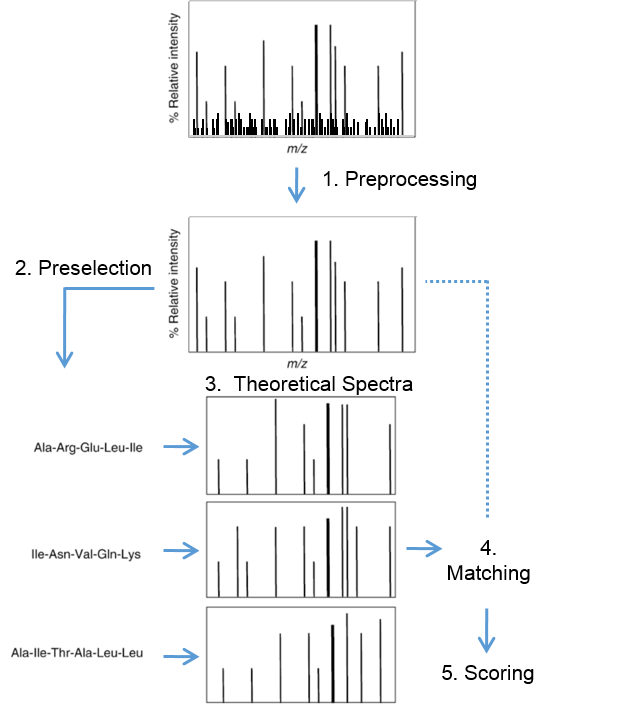

Figure 6: Process of computational identification of peptides from their fragment spectra

Previously we learned, that peptides fragment to create patterns characteristic of a specific amino acid sequence. These patterns are reproducible and, in general, predictable taking the applied fragmentation method into account. This can be used for computational identification of peptides from their fragment spectra. This process can be subdivided into 5 main steps: spectrum preprocessing, selection of possible sequences, generating theoretical spectra, matching and scoring (Figure 6). The first step is a preprocessing of the experimental spectra and is done to reduce noise. Secondly, all possible amino acid sequences are selected which match the particular precursor peptide mass. The possible peptides can but do not need to be restricted to a particular organism. A theoretical spectrum is predicted for each of these amino acid sequences. Matching and scoring is performed by comparing experimental spectra to their predicted corresponding theoretical spectra. The score function measures the closeness of fit between the experimental acquired and theoretical spectrum. There are many different score functions, which can be considered as the main reason of different identifications considering different identification algorithm. The most natural score function is the cross correlation score (xcorr) used by the commercially available search tool SEQUEST. One of the reasons the xcorr is so sensitive is because it involves a correction factor that assesses the background correlation for each acquired spectrum and the theoretically predicted spectrum from sequences within a database. To compute this correction factor, a measure of similarity is calculated at different offsets between a preprocessed mass spectrum and a theoretical spectrum. The final xcorr is then the correlation at zero offset minus the mean correlation from all the individual offsets.

Thus, the correlation function measures the coherence of two signals by, in effect, translating one signal across the other. This can be mathematically achieved using the formula for cross-correlation in the form for discrete input signals:

Equation 5

where x(i) is a peak of the reconstructed spectrum at position i and y(i) is a peak of the experimental spectrum. The displacement value 𝜏 is the amount by which the signal is offset during the translation and is varied over a range of values. If two signals are the same, the correlation function should have its maxima at 𝜏=0, where there is no offset. The average of the offset-correlation is seen as the average background correlation and needs to be subtracted from the correlation at 𝜏=0. It follows:

Equation 6

In practice many theoretical spectra have to be matched again a single experimental spectrum. Therefore, the calculation can be speed up by reformulating Equation 5 and Equation 6 and introduce a preprocessing step, which is independent of the predicted spectra.

Equation 7

For the preprocessed experimental spectrum y' it follows:

Equation 8

where:

Equation 9

Matching a measured spectrum against chlamy database

#r "nuget: BioFSharp, 2.0.0-beta4"

#r "nuget: BioFSharp.IO, 2.0.0-beta4"

#r "nuget: Plotly.NET, 4.2.0"

#r "nuget: BioFSharp.Mz, 0.1.5-beta"

#r "nuget: BIO-BTE-06-L-7_Aux, 0.0.10"

#if IPYNB

#r "nuget: Plotly.NET.Interactive, 4.2.0"

#endif // IPYNB

open Plotly.NET

open BioFSharp

open BioFSharp.Mz

open BIO_BTE_06_L_7_Aux.FS3_Aux

open System.IO

Step 1: Data acquisition and preprocessing

We load a single MS2 spectrum that is saved in a mgf file.

// Code-Block 1

let directory = __SOURCE_DIRECTORY__

let path = Path.Combine[|directory;"downloads/ms2sample.mgf"|]

downloadFile path "ms2sample.mgf" "bio-bte-06-l-7"

let ms2 =

BioFSharp.IO.Mgf.readMgf path

|> List.head

ms2

|

Here, the spectrum is already centroidized as shown in NB03c_Centroidisation.ipynb using the function

msPeakPicking. So we just visualize mass and intensity:

// Code-Block 2

let ms2Chart =

Chart.Column(ms2.Intensity, ms2.Mass)

|> Chart.withTemplate ChartTemplates.light

ms2Chart

|

Now, we will preprocess the experimental spectrum from our example. This is on the one hand to reduce noise, but also to make the measured spectrum more like the once we are able to simulate.

// Code-Block 3

let lowerScanLimit = 150.

let upperScanLimit = 1000.

let preprocessedIntesities =

Mz.PeakArray.zip ms2.Mass ms2.Intensity

|> (fun pa -> Mz.PeakArray.peaksToNearestUnitDaltonBinVector pa lowerScanLimit upperScanLimit)

|> (fun pa -> Mz.SequestLike.windowNormalizeIntensities pa 10)

let intensityChart =

Chart.Column(preprocessedIntesities, [lowerScanLimit .. upperScanLimit])

|> Chart.withTemplate ChartTemplates.light

intensityChart

|

Step 2: Preselecting the peptides of interest

Every MS2 spectrum is accompanied by a m/z ratio reported by the instrument. Additionally, we can estimate the charge looking at the isotopic cluster. We take the peptide "DTDILAAFR" from our previous notebook again. Our example has a measured m/z = 511.2691141 and a charge of z=2.

let peptideMass =

Mass.ofMZ 511.2691141 2.

peptideMass

|

From our previos notebook NB02b_Digestion_and_mass_calculation.ipynb, we know how to calculate all peptide masses that we can expect to be present in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii.

// Code-Block 4

let path2 = Path.Combine[|directory;"downloads/Chlamy_JGI5_5(Cp_Mp).fasta"|]

downloadFile path2 "Chlamy_JGI5_5(Cp_Mp).fasta" "bio-bte-06-l-7"

let peptideAndMasses =

path2

|> IO.FastA.fromFile BioArray.ofAminoAcidString

|> Seq.toArray

|> Array.mapi (fun i fastAItem ->

Digestion.BioArray.digest Digestion.Table.Trypsin i fastAItem.Sequence

|> Digestion.BioArray.concernMissCleavages 0 0

)

|> Array.concat

|> Array.map (fun peptide ->

// calculate mass for each peptide

peptide.PepSequence, BioSeq.toMonoisotopicMassWith (BioItem.monoisoMass ModificationInfo.Table.H2O) peptide.PepSequence

)

peptideAndMasses |> Array.head

|

However, we are only interest in possible amino acid sequences, that match the particular precursor peptide mass of our example spectrum with 1020.523675 Da. Additionaly, we should also consider a small measurement error.

// Code-Block 5

peptideAndMasses

|> Array.filter (fun (sequence,mass) -> mass > 1020.52 && mass < 1020.53)

|

In the previous notebook NB04a_Fragmentation_for_peptide_identification.ipynb,

we used functions that generate the theoretical series of b- and y-ions from the given peptide. Combined with the function

Mz.SequestLike.predictOf that generates theoretical spectra that fit the Sequest scoring algorithm.

// Code-Block 6

let predictFromSequence peptide =

[

peptide

|> Mz.Fragmentation.Series. yOfBioList BioItem.initMonoisoMassWithMemP

peptide

|> Mz.Fragmentation.Series.bOfBioList BioItem.initMonoisoMassWithMemP

]

|> List.concat

|> Mz.SequestLike.predictOf (lowerScanLimit,upperScanLimit) 2.

Step 3+4: Matching and Scoring

In the matching step, we compare theoretical spectra of peptides within our precursor peptide mass range with our measured spectra. We get a score which tells us how well the theoretical spectrum fits the given experimental spectrum.

// Code-Block 7

let sortedScores =

peptideAndMasses

|> Array.filter (fun (sequence,mass) ->

mass > 1020.52 && mass < 1020.53

)

|> Array.map (fun (sequence,mass) ->

sequence,predictFromSequence sequence

)

|> Array.map (fun (sequence,theoSpectrum) ->

sequence,BioFSharp.Mz.SequestLike.scoreSingle theoSpectrum preprocessedIntesities

)

|> Array.sortByDescending (fun (sequence,score) -> score)

sortedScores

|

Finally, we pick the sequence with the best score and are done for now. Notice however, that in a real world we would need to relate our score to the complete data set to get an idea of the overall quality and which numerical value we could trust.

Questions

- How does the Chart change, when you change the value of 'numberofwindows' from 10 to 20? What does this parameter specify? (Code-Block 3)

- What is the rational behind the normalization of measured spectra?

- Why are we adding the mass of water to the peptide sequence? (BioItem.monoisoMass ModificationInfo.Table.H2O) (Code-Block 4)

- In code block 6 you get a raw estimate on how many peptide sequences are candidates for a match, when given a certain mz. Given that one MS run can consist of up to 120.000 ms2 spectra, how many peptide spectrum matches do you have to perform? What does that mean for the performance of the application? Which parameters influence the size of the "search space"? (Code-Block 6)

- What happens when you choose different lower and upper scan limits?

- Visualize the distribution of scores using a histogram. (Code-Block 7)

<summary>Performs operations on <see cref="T:System.String" /> instances that contain file or directory path information. These operations are performed in a cross-platform manner.</summary>

Path.Combine(path1: string, path2: string) : string

Path.Combine(path1: string, path2: string, path3: string) : string

Path.Combine(path1: string, path2: string, path3: string, path4: string) : string

module List from Microsoft.FSharp.Collections

<summary>Contains operations for working with values of type <see cref="T:Microsoft.FSharp.Collections.list`1" />.</summary>

<namespacedoc><summary>Operations for collections such as lists, arrays, sets, maps and sequences. See also <a href="https://docs.microsoft.com/dotnet/fsharp/language-reference/fsharp-collection-types">F# Collection Types</a> in the F# Language Guide. </summary></namespacedoc>

--------------------

type List<'T> = | ( [] ) | ( :: ) of Head: 'T * Tail: 'T list interface IReadOnlyList<'T> interface IReadOnlyCollection<'T> interface IEnumerable interface IEnumerable<'T> member GetReverseIndex : rank:int * offset:int -> int member GetSlice : startIndex:int option * endIndex:int option -> 'T list static member Cons : head:'T * tail:'T list -> 'T list member Head : 'T member IsEmpty : bool member Item : index:int -> 'T with get ...

<summary>The type of immutable singly-linked lists.</summary>

<remarks>Use the constructors <c>[]</c> and <c>::</c> (infix) to create values of this type, or the notation <c>[1;2;3]</c>. Use the values in the <c>List</c> module to manipulate values of this type, or pattern match against the values directly. </remarks>

<exclude />

<summary>Returns the first element of the list.</summary>

<param name="list">The input list.</param>

<exception cref="T:System.ArgumentException">Thrown when the list is empty.</exception>

<returns>The first element of the list.</returns>

<summary>Contains operations for working with values of type <see cref="T:Microsoft.FSharp.Collections.seq`1" />.</summary>

<summary>Builds an array from the given collection.</summary>

<param name="source">The input sequence.</param>

<returns>The result array.</returns>

<exception cref="T:System.ArgumentNullException">Thrown when the input sequence is null.</exception>

<summary>Contains operations for working with arrays.</summary>

<remarks> See also <a href="https://docs.microsoft.com/dotnet/fsharp/language-reference/arrays">F# Language Guide - Arrays</a>. </remarks>

<summary>Builds a new array whose elements are the results of applying the given function to each of the elements of the array. The integer index passed to the function indicates the index of element being transformed.</summary>

<param name="mapping">The function to transform elements and their indices.</param>

<param name="array">The input array.</param>

<returns>The array of transformed elements.</returns>

<exception cref="T:System.ArgumentNullException">Thrown when the input array is null.</exception>

<summary>Builds a new array that contains the elements of each of the given sequence of arrays.</summary>

<param name="arrays">The input sequence of arrays.</param>

<returns>The concatenation of the sequence of input arrays.</returns>

<exception cref="T:System.ArgumentNullException">Thrown when the input sequence is null.</exception>

<summary>Builds a new array whose elements are the results of applying the given function to each of the elements of the array.</summary>

<param name="mapping">The function to transform elements of the array.</param>

<param name="array">The input array.</param>

<returns>The array of transformed elements.</returns>

<exception cref="T:System.ArgumentNullException">Thrown when the input array is null.</exception>

<summary>Returns the first element of the array.</summary>

<param name="array">The input array.</param>

<returns>The first element of the array.</returns>

<exception cref="T:System.ArgumentNullException">Thrown when the input array is null.</exception>

<exception cref="T:System.ArgumentException">Thrown when the input array is empty.</exception>

<summary>Returns a new collection containing only the elements of the collection for which the given predicate returns "true".</summary>

<param name="predicate">The function to test the input elements.</param>

<param name="array">The input array.</param>

<returns>An array containing the elements for which the given predicate returns true.</returns>

<exception cref="T:System.ArgumentNullException">Thrown when the input array is null.</exception>

<summary>Returns a new list that contains the elements of each the lists in order.</summary>

<param name="lists">The input sequence of lists.</param>

<returns>The resulting concatenated list.</returns>

<summary>Sorts the elements of an array, in descending order, using the given projection for the keys and returning a new array. Elements are compared using <see cref="M:Microsoft.FSharp.Core.Operators.compare" />.</summary>

<remarks>This is not a stable sort, i.e. the original order of equal elements is not necessarily preserved. For a stable sort, consider using <see cref="M:Microsoft.FSharp.Collections.SeqModule.Sort" />.</remarks>

<param name="projection">The function to transform array elements into the type that is compared.</param>

<param name="array">The input array.</param>

<returns>The sorted array.</returns>