NB04a Fragmentation for peptide identification

- Understanding MS2 spectra: From peptide to fragment

- Simulate MS2 Fragmentation

- Questions

- References

Understanding MS2 spectra: From peptide to fragment

The currency of information for identification in MS-based proteomics is the fragment ion spectrum (MS/MS spectrum) that is typically derived from the fragmentation of a specific peptide in the collision cell of a mass spectrometer. Peptides produce fragments that provide information on their amino acid sequence. The correct assignment of such a spectrum to a peptide sequence is the central step to link m/z values and ion intensities to biology (Nesvizhskii et al. 2007).

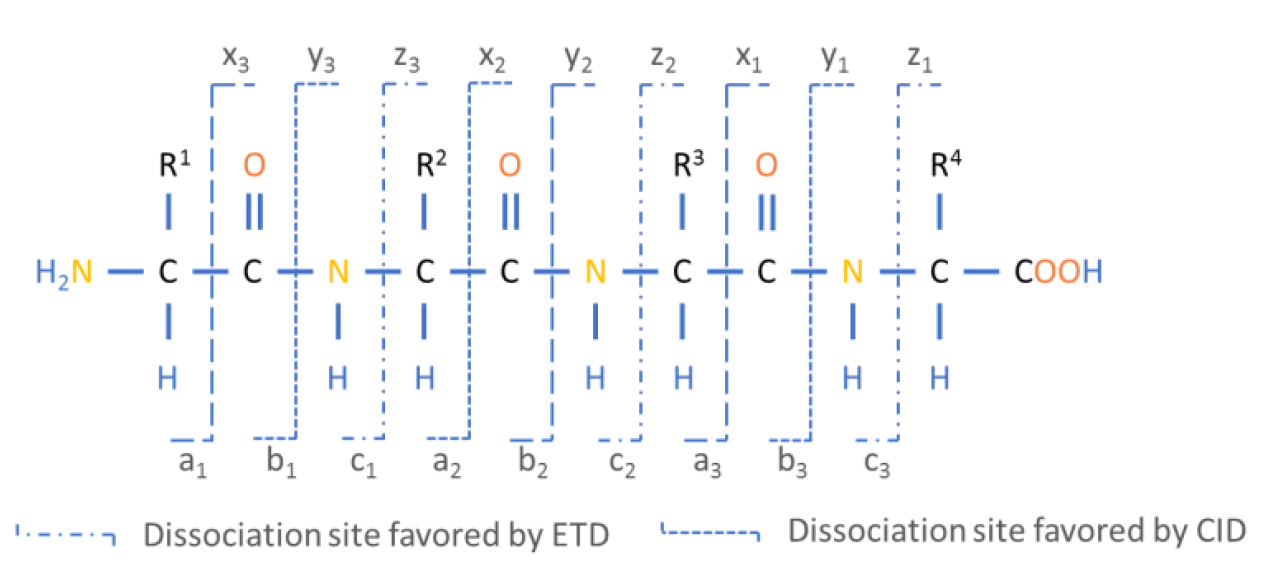

Figure 5: The Roepstorff-Fohlmann-Biemann nomenclature of fragment ions.

N-terminal and C-terminal peptide fragments result of dissociation of electron bonds along the peptide backbone.

During the unimolecular peptide ion dissociation processes, different chemical reactions can lead to different types of product ions. The types of ions observed in MS/MS experiments depend on the physicochemical properties of the amino acids and their sequence, on the amount of internal energy, and on the peptide’s charge state. In addition, product ion formation is strongly influenced by the fragmentation method (Medzihradszky 2005). The most widely used fragmentation methods today are low-energy collision-induced dissociation (CID) (Johnson et al. 1987) and electron transfer dissociation (ETD) (Mikesh et al. 2006). These methods favor fragmentation along the peptide backbone and result in an N-terminal prefix fragment and a C-terminal suffix fragment. The standard nomenclature for the C-terminal fragments is x, y and z whereas the corresponding N-terminal fragments are denoted as a, b and c depending on the position where the breakage occurs at the peptide backbone level. The numbering of each fragment starts from the N-terminus for a,b,c series and from the C-terminus for x,y,z series (Figure 4). One should keep in mind that during parent ion selection many of the same peptide ions are selected and dissociated into fragments, with the resulting fragment ions having different relative abundances according to the preferred fragmentation reaction. In addition to the fragmentation along the peptide backbone, fragment ions containing the amino acids R, K, N, or Q can lose ammonia (-17 Da) and are then denoted a, b and y*. Fragments containing the amino acids S, T, E, or D may lose water (-18 Da) and are then denoted a°, b° and y°. These losses do not change the charge of the ions and are observable as natural losses (Forner et al. 2007, Steen and Mann 2004).

#r "nuget: BioFSharp, 2.0.0-beta5"

#r "nuget: BioFSharp.IO, 2.0.0-beta5"

#r "nuget: Plotly.NET, 4.2.0"

#r "nuget: BioFSharp.Mz, 0.1.5-beta"

#if IPYNB

#r "nuget: Plotly.NET.Interactive, 4.2.0"

#endif // IPYNB

open Plotly.NET

open BioFSharp

Simulate MS2 Fragmentation

For the simulation we first define a short peptide. The peptide we take for this example is from rbcL.

// Code-Block 1

let peptide =

"DTDILAAFR"

|> BioList.ofAminoAcidString

peptide

|

In the Mz namespace of BioFSharp, we can find a function that can

generate the theoretical series of y-ions from the given peptide. This function provides a lot of information, but we are only interested

in the mass. Notice, that we do not know the intesity of the fragment ions and just use '1.' for simulation.

// Code-Block 2

let ionSeriesY =

peptide

|> Mz.Fragmentation.Series.yOfBioList BioItem.initMonoisoMassWithMemP

|> List.map (fun aac -> aac.MainPeak.Mass,1.)

ionSeriesY

|

Similarly, we can simulate the b-ion series.

// Code-Block 3

let ionSeriesB =

peptide

|> Mz.Fragmentation.Series.bOfBioList BioItem.initMonoisoMassWithMemP

|> List.map (fun aac -> aac.MainPeak.Mass,1.)

ionSeriesB

|

Now, we can just plot the simulated data and look at our theoretical spectrum.

// Code-Block 4

let ionChart =

[

Chart.Column (ionSeriesB, Name = "b ions")

Chart.Column (ionSeriesY, Name = "y ions")

]

|> Chart.combine

ionChart

|

Questions:

- Why are ms1 spectra not sufficent for peptide identification?

- How can fragmentation help with this?

- For an oligopeptide consisting of 3 amino acids, roughly estimate the number of possible fragments if only cosidering b/y fragments or abc/xyz fragments. What advantages and disadvantages might only considering b/y fragments have?

References

- Nesvizhskii, A. I., Vitek, O. & Aebersold, R. Analysis and validation of proteomic data generated by tandem mass spectrometry. Nature methods 4, 787–797; 10.1038/nmeth1088 (2007).

- Medzihradszky, K. F. Peptide sequence analysis. Method Enzymol 402, 209–244; 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)02007-0 (2005).

- Johnson, R. S., Martin, S. A., Biemann, K., Stults, J. T. & Watson, J. T. Novel fragmentation process of peptides by collision-induced decomposition in a tandem mass spectrometer: differentiation of leucine and isoleucine. Anal. Chem. 59, 2621–2625; 10.1021/Ac00148a019 (1987).

- Mikesh, L. M. et al. The utility of ETD mass spectrometry in proteomic analysis. Biochimica et biophysica acta 1764, 1811–1822; 10.1016/j.bbapap.2006.10.003 (2006).

- Forner, F., Foster, L. J. & Toppo, S. Mass spectrometry data analysis in the proteomics era. Curr Bioinform 2, 63–93; 10.2174/157489307779314285 (2007).

- Steen, H. & Mann, M. The ABC's (and XYZ's) of peptide sequencing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 699–711; 10.1038/nrm1468 (2004).

module List from Microsoft.FSharp.Collections

<summary>Contains operations for working with values of type <see cref="T:Microsoft.FSharp.Collections.list`1" />.</summary>

<namespacedoc><summary>Operations for collections such as lists, arrays, sets, maps and sequences. See also <a href="https://docs.microsoft.com/dotnet/fsharp/language-reference/fsharp-collection-types">F# Collection Types</a> in the F# Language Guide. </summary></namespacedoc>

--------------------

type List<'T> = | ( [] ) | ( :: ) of Head: 'T * Tail: 'T list interface IReadOnlyList<'T> interface IReadOnlyCollection<'T> interface IEnumerable interface IEnumerable<'T> member GetReverseIndex : rank:int * offset:int -> int member GetSlice : startIndex:int option * endIndex:int option -> 'T list static member Cons : head:'T * tail:'T list -> 'T list member Head : 'T member IsEmpty : bool member Item : index:int -> 'T with get ...

<summary>The type of immutable singly-linked lists.</summary>

<remarks>Use the constructors <c>[]</c> and <c>::</c> (infix) to create values of this type, or the notation <c>[1;2;3]</c>. Use the values in the <c>List</c> module to manipulate values of this type, or pattern match against the values directly. </remarks>

<exclude />

<summary>Builds a new collection whose elements are the results of applying the given function to each of the elements of the collection.</summary>

<param name="mapping">The function to transform elements from the input list.</param>

<param name="list">The input list.</param>

<returns>The list of transformed elements.</returns>